Robot Dogs and the Long Road to EIDOLWARE

In 2015, I came across a New York Times video about people in Japan holding funerals for their Sony Aibo robot dogs. These were ceremonies at a Buddhist temple, with a monk presiding. Sony had, at the time, discontinued the Aibo line and stopped offering repairs, so when these robot dogs finally broke down, that was it. They were gone. And their owners treated that loss the same way you’d treat losing a pet.

What I found interesting was that this wasn’t just people being sentimental. There’s a long tradition in Japanese culture, rooted in Shinto beliefs, that all things have a spirit or soul, even man-made objects. There’s even a concept called tsukumogami, the idea that everyday household objects can acquire a spirit after about a hundred years of faithful use. Shrines in Japan still hold ceremonies to honor old tools, needles, even dolls, thanking them for their service before letting them go. So when those Aibo owners held funerals for their robot dogs, they weren’t being irrational. They were drawing from something much older than Sony.

When I saw that, my first thought was, “Why does someone feel that way?” Because clearly these people weren’t confused about what an Aibo was. Somewhere along the way, through years of daily interaction, “feeding” it, playing with it, watching it develop its own quirky behaviors, something shifted. The machine became something more to them. And I kept asking myself: is it human nature to give life into inanimate objects?

A Short Comic That Refused to Stay Short

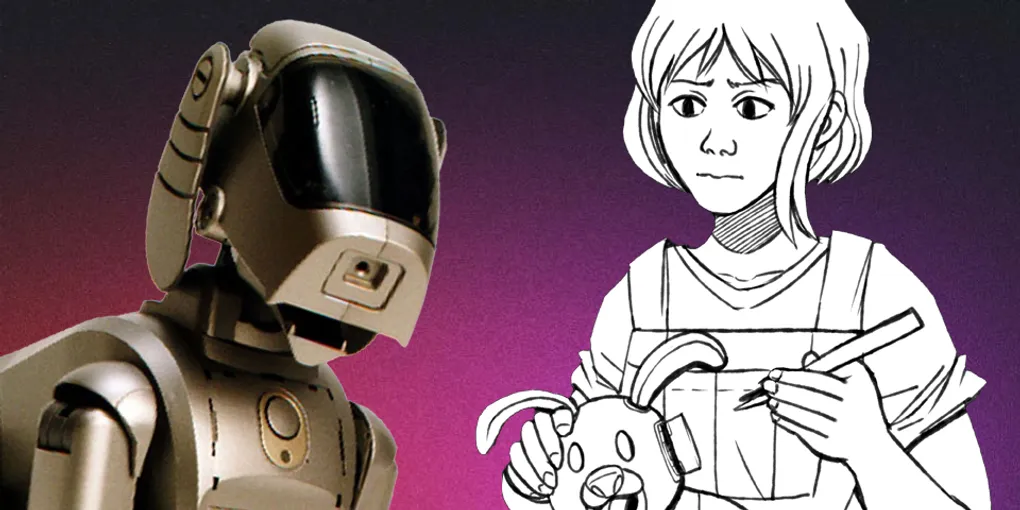

I started sketching out a short comic based on that feeling. The idea was simple: a little girl walks into what looks like a veterinarian’s office, carrying a pet kennel. You’re meant to assume she’s bringing in a sick animal. But the reveal at the end is that it’s a robot dog, and she’s not there to get it fixed. She’s there to bring it back to life. There’s a difference between those two things, at least to her, and I think that difference is interesting.

The problem was, once I started drawing it, my brain wouldn’t stop expanding the premise. If people are already holding funerals for relatively simple robot dogs in 2015, what happens when the technology gets significantly better? Would people start seeing souls in their everyday electronics? Is there a point where a machine crosses some invisible threshold and becomes, I don’t know, a companion? A friend? Something you mourn?

All of those questions turned what was supposed to be a quick comic into something much bigger. I started developing a graphic novel called “Demonware” and began drawing early concepts of the main character, Anna, her occupation as an engineer, and the kind of world she would live in. The setting was near-future, technology-saturated, full of unintended consequences from things people built with good intentions.

I had the world. I had the themes. What I didn’t have was a clear sense of who Anna actually was as a person. I knew her job and her circumstances, but her personality and voice were still forming in my head. And for a graphic novel, where you need to commit to a character’s voice from the very first page, that was a problem.

Why It Became a Game

A few years later, I was making a big career shift from working as an illustrator to becoming a software engineer. And honestly, working in tech changed my entire perspective on the themes I’d been exploring. Drawing pictures of a world where technology creates problems is one thing. Actually writing code every day, watching how software gets built and how people interact with it, seeing firsthand how a few lines of code can reshape someone’s daily life… that gave me so much more to say about the relationship between people and technology.

I started thinking that Demonware might actually work better as a game rather than a graphic novel. Part of it was practical: I wanted to improve both my art and my programming skills simultaneously, and making a game would force me to do both. But the bigger reason was Anna. In a comic, I’d need her voice nailed down before I drew a single panel. In a game, she could be the player character. Her personality could come through in how she reacts to the world around her, how she handles the bizarre situations thrown at her. I could figure out who she was through the process of building the game itself, and the player would get to discover her alongside me.

The first version was a turn-based RPG built in RPG Maker. It functioned, but something about it felt off. The pacing was too slow. Anna’s world was supposed to feel chaotic, fast, full of things spiraling out of control. Repairing robot dogs and having everyone stand in neat rows and politely wait their turn to attack didn’t capture any of that energy.

So in 2022 I moved everything over to Construct 3 and rebuilt the game as an action RPG. Real-time combat, reactive movement, the kind of game where you’re constantly making split-second decisions. I was inspired by games like Terranigma and CrossCode. That fit. It felt like the version of the game that this world actually needed.

And the funny thing is, it worked. As I kept building the game and writing the characters around her, Anna’s voice finally showed up. She’s someone who’s out of her element, trying to navigate a world she doesn’t fully understand, and her reactions to the absurdity around her feel real because she’s figuring it out as she goes. I didn’t find her by sitting down and writing a character bible. I found her by putting her in weird situations and seeing what she’d do.

How Robot Dogs Turned Into an Anime Convention

While I was deep in prototyping, the real world decided to get a lot weirder than any fiction I could write. Cryptocurrency went from a niche internet thing to a full-blown cultural phenomenon, complete with overnight millionaires, elaborate scams, and communities of people who were absolutely convinced they were building the future of civilization. Then AI tools started becoming part of everyday life, and suddenly everyone, and I mean everyone, had strong opinions about what machines should and shouldn’t be allowed to do.

The themes I’d been thinking about since that robot dog video were suddenly everywhere, but louder, stranger, and more absurd than anything I’d imagined. I found myself wanting to do more than just explore these ideas thoughtfully. I wanted to make fun of them. Because honestly, when you step back and look at the state of things, a lot of it is genuinely ridiculous. And I think there’s value in pointing that out while still caring about the real questions underneath.

Demonware became EIDOLWARE. The story pivoted from repairing robot dogs to something much bigger in scope: a satirical action RPG about AI, fandom culture, cryptocurrency, and what happens when people’s interests and obsessions start running their lives instead of enriching them. But that original spark, the idea that people can form genuine emotional connections with technology, and that those connections deserve to be taken seriously even when they seem absurd from the outside, that’s still at the core of everything.

It’s just wrapped in an underground anime convention, a crypto-billionaire who wears a fedora and calls himself a paladin, and a cast of characters who are all completely certain they’re the most important person in the room.

Where Things Are Now

EIDOLWARE is an action RPG about Anna Lam, a former AI engineer who descends into FedoraCon, a permanent underground anime convention powered by experimental holographic technology, to investigate her mentor’s suspicious death. It’s satirical, it’s strange, and it’s the game I’ve been slowly building toward ever since a New York Times video about robot dog funerals made me ask a question I still haven’t fully answered.

This is the first game from FATBAT Studio, our indie art collective. I just have a story I’ve been carrying around for a long time and I want to tell it. I hope people enjoy playing it.

More updates are on the way. Next time, I’ll get into my experience learning the differences between software development and game development, and how that process shaped EIDOLWARE.

- Ryv, FATBAT Studio